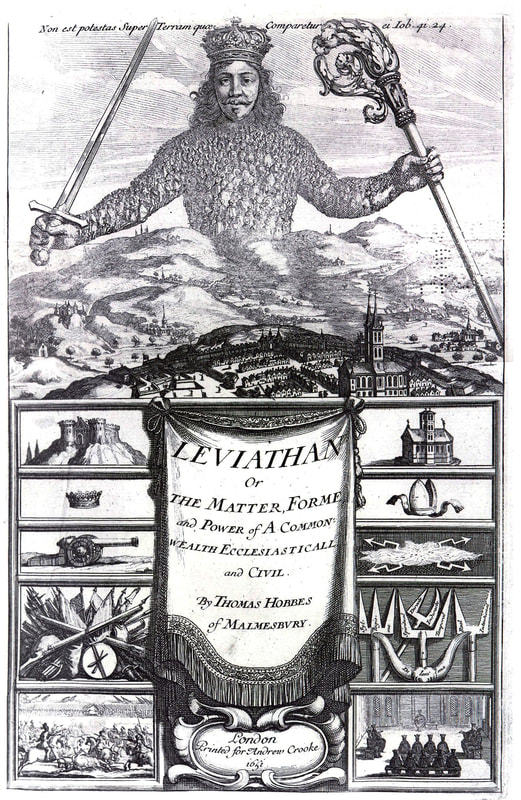

In the constrained vision, people are driven by their desires and are, in the main, unable to resist pursuing those desires "except when inherent social constraints are forcibly imposed on them as individuals through various social mechanisms such as prices... or moral traditions and social pressures...."[4] Our ability to understand the forces driving our behavior is limited, and so theorists with a constrained vision prefer social mechanisms and systems that evolve, like markets and religions and common law. These systems build up wisdom or social knowledge over time by aggregating the tradeoffs made by individuals pursuing their own interests. Skeptical of our ability to design solutions individually or in groups, constrained theorists rely on the evolution of social systems over time, and favor the trade-offs reflected by such systems over solutions or strategies designed by experts or groups of experts.

Prices are a great example of the type of systemic knowledge embodied in Sowell's constrained vision. Suppose demand increases for a product, causing a reduction in available supply. Producers make trade-offs with regard to the allocation of resources that would be required to increase supply. Suppose also that, in our ideal case, the resources necessary to increase supply of the product in question command a higher price when used for other purposes. Without these additional resources, supply of the original product stays the same. Its market price rises due to the market forces of supply and demand, eventually leading to a reduced level of demand at the higher price. As the price rises, people make trade-offs in their budgets to either justify paying the higher price or to spend their money on a alternative product. In this ideal case, no one has to make a decision for the market to adjust the price of a good. Constrained theorists would say no person or group of persons is capable of reasoning to the price that optimizes use of all resources. Critically, the role of social institutions for "constrained vision" thinkers is to mirror and convey the kinds of systemic adjustments we see in this ideal market example.

The unconstrained vision, on the other hand, sees no inherent inability on the part of people to constrain themselves from acting selfishly or to understand the world around them. People can act from a sense of social responsibility instead of just from self-interest. Moreover, we can trust the rational analyses provided by experts and leaders to define what actions would achieve desirable social ends. Since we are capable of understanding cause and effect, we should use our rational capacities to design and implement the best solutions to current problems. Over time, people will accept rational solutions and act in accordance with them, even in the absence of compulsory mechanisms.

Continuing with our previous example on prices, we can find an example in which articulated rationality of experts provides a solution that illustrates the unconstrained vision. Imagine the market in a large city sets the price for a gallon of gasoline to cover the costs of finding and drilling for oil, refining the oil into gasoline, transporting the gasoline to the consumer, and reasonable profit for the various entities in the supply chain. At that market price, so many people are able to buy so much gasoline that the roads are soon hopelessly congested with traffic. Furthermore, the heavy volume of traffic is causing rapid wear on the existing roads and a serious air pollution problem. The traffic congestion, excessive wear on existing roads, and pollution are not factored in to the market price of the gallon of gasoline. They are external to the factors affecting the cost of providing the gasoline to the consumer. To address these externalities, the city council decides to add a tax to each gallon of gasoline. This tax artificially increases the price of gasoline, reducing demand and consumption (and traffic). Furthermore, the tax provides a pool of money the city can use to repair existing roads, to create a mass transit system, and to educate the public on ways to reduce air pollution. People pay the tax because they have to, but over time more and more adopt public transportation voluntarily because they know it is better for the community in terms of reducing traffic and air pollution.

The constrained and unconstrained visions define a spectrum of beliefs about human nature. Few, if any, rely exclusively on one or the other vision. Most of us rely on both visions to some extent. We find one or the other more applicable in different realms, or we may be more or less consistent in the application of a vision. According to Sowell, even Marxism is a hybrid vision.

To differentiate between theories that are mostly representative of one or the other vision, Sowell uses a two-pronged test. The location of discretionary power in an institution or theory is one part of the test. The other part is the manner in which the product of that discretionary power is applied in society. For constrained theories, the locus of discretion lies with large numbers of individuals making independent tradeoffs in pursuit of their own interests. The mode of applying all of these individual acts of discretion is indirect, through mechanisms like the "invisible hand" Adam Smith uses to describe how the market regulates supply and demand. For unconstrained theories, the locus of discretion is with experts or groups of experts who deliberately develop and implement rational solutions to achieve optimal solutions for society overall. The mode of application is direct, through laws or whatever administrative instrumentality is available for such social engineering. [5]

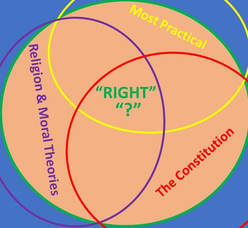

Over the past several blogs, we have examined the philosophical roots of our Constitution. Magna Carta represented a dramatic turn away from the notion of divine right, starting the logical process of reassigning sovereign power from one or more elites to all members of the polity. Later, state of nature theorists attempted to justify various forms of government by reasoning from their conception of how people would behave in the absence of a government. From the Enlightenment to the 20th century, we see how different conceptions of human nature lead to very different notions of what government should look like. We can see the impact of Locke's state of nature on the founders of the United States. Sowell's conflict of visions presents a fascinating perspective on this tradition, and a convergence of sorts with our parallel inquiry into how we can know whether something is right or true. We'll take that up in our next blog.

[1] Sowell, Thomas, A Conflict of Visions, William Morrow and Company, New York, NY, 1987, pp. 18-9.

[2] ibid, pp. 97-8.

[3] ibid, pp. 38-9, 95-6.

[4] ibid, p. 100.

[5] ibid, pp. 96-108

RSS Feed

RSS Feed