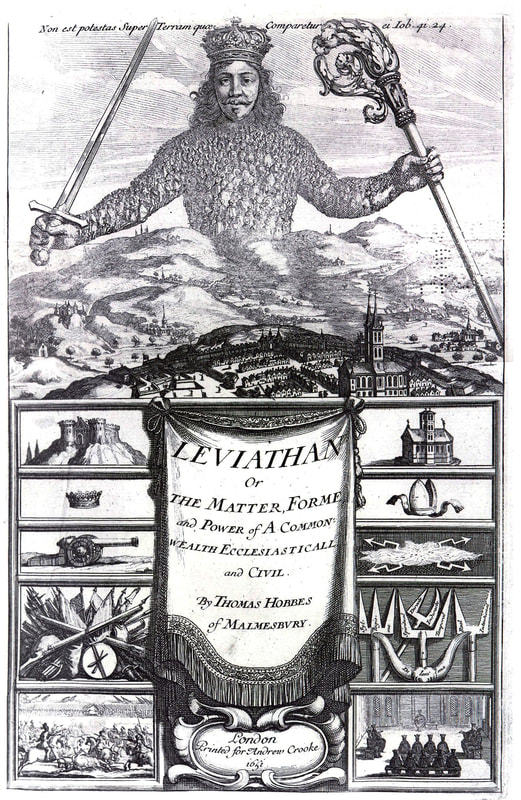

By the middle of the seventeenth century, Thomas Hobbes used these concepts to justify the absolute power of the monarch. In Leviathan, published in 1651, Hobbes depicted the condition of humans without government of any kind. Hobbes' concept of this "state of nature" was a war of all against all. According to Hobbes, the benefit of exiting such a state required the surrender of individual liberty to a government with absolute power.

Other philosophers almost immediately reacted to Hobbes' depiction of the state of nature. Jean-Jacques Rousseau published his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality in 1754, and his depiction of the state of nature was precisely opposite that of Hobbes. Rousseau felt that humans in such a condition would be living in accord with what he termed "uncorrupted morals." The introduction of society was, for Rosseau, where corruption enters. He opens his treatise entitled Social Contract Theory with the statement, "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains."

Within a few decades, John Locke had proposed yet another alternative vision of the state of nature as a place governed by a natural law that afforded everyone an equal right to life, liberty and property. Locke published his Two Treatises of Government around 1689, although he did so anonymously. Needless to say, the social contract emerging from that state of nature was quite different from what Hobbes had envisioned. And it is this version of the social contract that is most often associated with the vision of the founders of the American republic, although the version published in 18th century America was incomplete.

The point here is not to endorse any one version of Enlightenment social contract theory. Rather, I think we should observe the fact that early social contract theorists injected different views of human nature into a state of nature and used that mechanism to generate a logical argument for a form of social contract--and hence for a form of government. And nearly everyone agrees the "state of nature" is a hypothetical construct rather than any condition that actually existed. Attempting to defend Locke's view of human nature, or Hobbes', or Rousseau's, reminds me of the old story of the three blind men describing an elephant. The man who grasps the trunk proclaims that the elephant is like a snake, the one who touches the side asserts that the elephant is like a wall, and the one who hugs a leg is convinced the elephant is like a tree. None of them are completely right as individuals, but they each have a piece of the truth. Together, they provide a better approximation of "right" than any of them do alone.

Theorists modified the idea of a state of nature in the twentieth century to make significant improvements to the basic ideas expressed by the Enlightenment philosophers. We'll take up that thread in our next blog.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed