At the same time, slavery was the original sin of the American Republic--the glaring hypocritical exception to the founding principle that we are all endowed with inalienable rights. Many of the founders recognized that hypocrisy, but they needed the vote of at least one slave state to achieve the ratification requirement of nine states: two-thirds of the thirteen states. And in fact, they probably needed more than that, given that the Articles of Confederation under which the states had operated since 1781 required the unanimous consent of all states. In other words, the Constitution may have been ratified if only the minimum number of states had approved it, but it is questionable whether the non-approving states would have cooperated under the new framework. As it happened, due to a number of compromises that gave the slave-holding states a disproportionate representation in Congress and restricted the power of the federal government to ban the importation of slaves for 20 years, all thirteen states did ratify the Constitution.

And the federal government did ban the importation of slaves at the earliest possible moment allowed by the Constitiution. But by that time, importation was no longer necessary to sustain the practice of slavery. And despite fervent hopes on the part of some of the founders that the example of non-slave states banning the practice of slavery would inspire a universal ban, there was really no chance that was ever going to happen. So the country moved through the first half of the 19th century, achieving a series of precarious balancing compromises. Time and again, the protests against the immorality of slavery clashed with the representative power of the slave states in Congress. First the Missouri Compromise, then the Compromise of 1850, held out the hope, for some at least, that time would allow the country to outgrow the slave legacy without bloodshed.

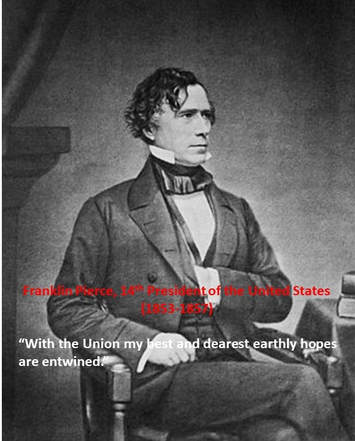

Then came President Pierce. And the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise, enraged the abolitionists in the north and led to widespread violence and the breakdown of democratic processes in the new territories. Now, instead of a strong declaration of the will to use federal power to defeat and punish secessionists, like the declarations made by Presidents Jackson and Taylor (both southerners), we had Franklin Pierce and his "best and dearest earthly hopes." In spite of a congressional investigation that found widespread fraud had illegally tilted elections in favor of slave-holders, Pierce sent the Army in--not to re-establish proper order through martial law--but to disband the legislature elected by anti-slave settlers in Topeka. The violence continued to spin out of control, and further compromise became more and more unlikely.

Of course, for the people suffering under the yoke of slavery, it might seem that another compromise itself would have been a moral failure as great as slavery itself. Sixty years after the ratification of the Constitution, sixty years after the compromises that enabled the birth of an American Republic proclaiming inalienable rights for all while denying them to African Americans, perhaps time had simply run out. But I think I would feel better about President Pierce if he had at least tried to use the power of the federal government to enforce legal process over gang violence in the Kansas and Nebraska territories.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed