So we know we exist. Beyond that we start making choices. We are confronted with experiences that we see, hear, touch, taste and smell. We can all agree that our individual perceptions of experience are imperfect. Those perceptions are sufficiently warped by emotion and bias in many cases to prevent agreement on the content and meaning of any given experience. We need a standard for truth that we can apply together to help us make decisions. How can we leverage what we know to determine what is truth and what is illusion, to differentiate between facts and fake news? I want to answer that question. To do so, I will return to Plato and Aristotle briefly, first to highlight the twin traditions of idealism and empiricism they handed down to western civilization, and then to explore how their common roots in the Pre-Socratic philosopher Pythagoras give us our modern foundation for truth.

The history of philosophy emphasizes the difference between the idealism of Plato's Theory of Forms and the empiricism of Aristotle. Plato believed the only real things were Forms that existed in a realm that we could not perceive with our senses but that we could access through reason. According to Plato, the objects we experience with our senses were not real in themselves, but only to the extent that they were reflections or copies of the ideal, unchanging Forms. After Plato's death, Aristotle left Athens and became the tutor of Alexander the Great. He abandoned Plato's Theory of Forms, adopting the philosophy that things we experience are real in themselves--a fusion of form and matter. Aristotelian forms were more like our common notion of DNA--internal blueprints that drive our growth. An oak tree is a good oak tree to the extent that it manifests the characteristics of oak trees--growing from an acorn, reaching a characteristic size with a certain kind of bark and leaves. A human is a good human to the extent that she manifests the characteristics of the human form--that of a social, rational animal. There are indeed significant differences in the philosophies of the master and his student. But, from the perspective of a theory of knowledge and a standard for truth, the important focus is not on how the two men differed, but how they agreed.

The views expressed by Plato and Aristotle agree in an interesting way. Both men believed that knowledge is not only possible, but that it is important to living a proper human life. This tells us something about what Plato and Aristotle believed regarding the nature of knowledge and truth--it implies they believed knowledge and truth correspond with or are coherent with the world in some way. If this was not true, there would be no way that knowledge and truth could be important to living a good human life. If things we can know to be true do not correspond with the world of experience, or if they are not coherent with the world of experience, then attempting to use knowledge and truth to live a better life would be like trying to use a street map of Pittsburgh to get from point A to point B in Salt Lake City. Things we can know to be true help us to live better lives only if knowledge and truth have the attributes of correspondence to the world we experience or coherence with the world we experience or both. And with correspondence and coherence comes the power to predict--we can use things we know to be true to calculate the effects and consequences of our actions.

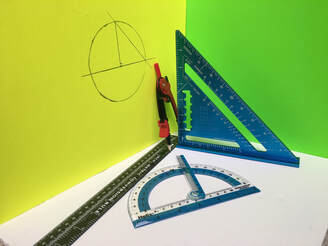

Plato and Aristotle did not arrive at the relationship between truth and world of experience on their own. They inherited their concepts of knowledge and truth from a tradition that went back at least 300 years to Pythagoras of Samos--a tradition deeply rooted in mathematics as the purest form of knowledge and the language underlying the observed universe. Pythagoras had taken the ancient set square, used to true up the perpendiculars in the construction of temples and palaces for thousands of years, and had proven a universal relationship existed in the proportions of the lengths of the sides associated with the right angle. He had proven that the sum of the areas of squares constructed with the two shorter sides always equalled the area of the square constructed using the hypotenuse. The Pythagorean Theorem was the archetype of knowledge and truth. Here was a product of reason deeply tied to the world of experience and nature that we all share. Here was a fact consistent with every observation, from the crystalline structures of naturally occurring elements to the tools used to construct the pyramids. Here was a theorem revealing--through correspondence or coherence or both--eternal relationships in the structure of the universe that could be used to predict and build. By the time of Plato, Euclid had expanded on Pythagoras' work and published his system of geometry and geometric proofs. [1]

A common modern definition of knowledge is "justified, true belief." There are three elements to this definition. To qualify as knowledge, a proposition has to be something in which we believe. Mere belief is a pretty low bar. We all have beliefs. We disagree with each other about whose beliefs are better or more true. Knowledge must rely on something more. Another element in our definition of knowledge is that it must be justified belief. That is somewhat better than belief alone--by adding the requirement for justification, we have to be able to offer reasonable grounds for our belief. But even this is not enough, as we can all offer reasons to believe things that are different from and inconsistent with what others have reason to believe. There must be a stricter requirement to differentiate knowledge from belief, and that leads us to the requirement for truth. When we say that something qualifies as knowledge because it is justified true belief, the assertion of truth is a claim about the relationship between the proposition we are considering and the world of experience that we all share. We are asserting that the proposition corresponds with the world of experience or is coherent with the world of experience, or both, in the same way as the Pythagorean Theorem.

Things are not true because we want them to be true, or because someone we like tells us they are true, or even because we all agree that they are (or should be) true. Things are true if and only if they stand in a certain relationship to the world of experience we all share. True things correspond to the world of experience, or are coherent with the world of experience, or both. Since the world of experience, as I am using that term, is a world we all share, then true things are also independently verifiable through their effects, or predicted effects.

[1] The description of Pythagoras' work is taken from Jacob Bronowski's book The Ascent of Man, and from the BBC television series based on that book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed