Institutional Racism and Sexism in America

It should not come as a surprise to anyone when I assert that institutional racism and sexism were baked into the original fabric of the United States. I don’t state that as an advocate for so-called “cancel culture.” I am not lamenting it or judging it in any way. I am simply stating a fact as a starting point in this essay. My moral view of that fact is irrelevant to the purpose of this essay. In this essay, I will use the fact that the government of the United States was born as a racist, sexist institution as support for my conclusion: that institutional racism and sexism still exist in the United States, albeit to a lesser degree, and that the continued manifestations of institutional racism and sexism in 2020 should be morally intolerable for all Americans.

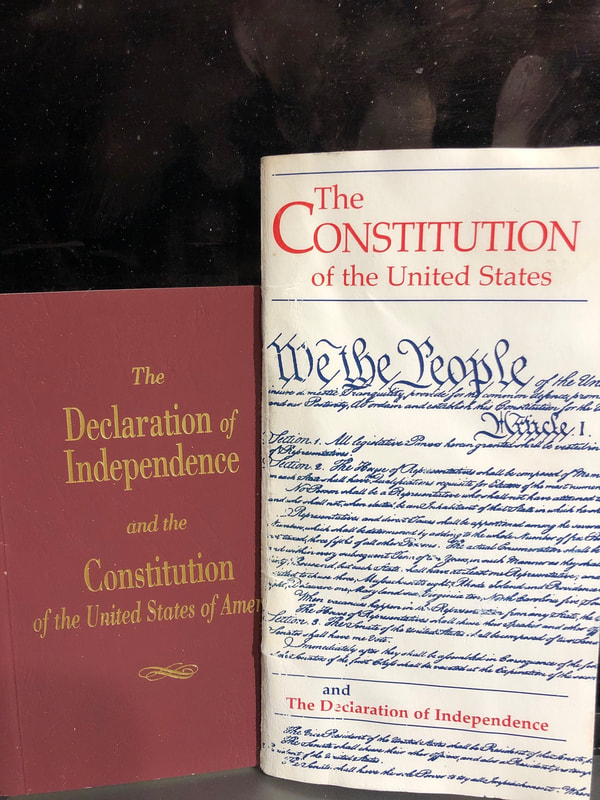

I don’t think any reasonable person can deny my starting point. Look at the picture of the signing of the Constitution. The only people in the picture are white men.

Read the words of the original Constitution. They very clearly allow slavery, and the continuation of importing slaves, and the counting of slaves as “three fifths” of a person for purposes of representation in Congress. “Indians not taxed” are excluded from being counted for purposes of representation. Ironically, women are not mentioned. Presumably, because the Declaration only states that “all Men are created equal,” the authors of the Constitution did not feel it necessary to explicitly address women. But the Constitution effectively denies equal rights to all three classes—slaves, Indians, and women. That is clear because it requires separate amendments and laws in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to abolish slavery and grant equal rights to former slaves, Indians, women and people of color. It is a simple fact, therefore, that the political and social institutions of the United States were racist and sexist at the time of the drafting and ratification of the Constitution. [House Document 112-129, The Constitution of the United States with Index and The Declaration of Independence, 25th Edition, 2012].

Those who hold that there is no institutional racism and sexism in the United States today must, therefore, believe that something has happened since the drafting and ratification of the Constitution that has removed the original problem. Indeed, we can point to the XIIIth, XIVth, and XVth Amendments to the Constitution as ending slavery, affording equal protection of the law to all persons, and explicitly granting former slaves the right to vote in 1865, 1868, and 1870, respectively. But clearly, this change to the supreme positive law of the United States did not guarantee compliance at the level of state laws and practices.

The 100 years after the Civil War were full of examples of domestic terrorism and murder against African Americans. The federal government effectively looked the other way as the Constitution was ignored in some cases and addressed with inadequate half measures to preserve segregation in others. Violence sometimes erupted into major incidents like white mobs leveling the “Black Wall Street” in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921 or the black town of Rosewood, Florida in 1923.

Women and Native Americans saw their rights formally recognized in the XIXth Amendment (1920) and the Indian Citizenship Act (1924), respectively. In practice, these changes in law did not magically change the treatment of women and Native Americans in every aspect of society. Social prejudices persist even when laws change. When programs like the New Deal, the GI Bill and Veterans home loans seemed to promise economic advancement without regard to race, social practices and governmental policies ensured a preservation of the status quo in a way that systemically took advantage of African Americans and other people of color, holding them at a lower level of economic achievement. Social Security was originally designed to exclude farm workers and domestic workers—exclusions that disproportionately affected black Americans. In 1950, “the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ code of ethics warned that ‘a Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood… any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values.” The federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation was an active participant in preserving these racial restrictions. [Coates, Ta-Nehisi, We Were Eight Years in Power, pp. 185-88]

The period from 1954 to 1964 saw another series of major changes to public law that seemed to signal real progress towards a society that was not racist. In Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Supreme Court ruled that state laws segregating public schools were unconstitutional. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 explicitly specified the equal rights for people of all races that had been systemically denied to people of color previously. Violence erupted in many parts of the country as the federal government sought to enforce these rulings. Ironically, the states failed to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) that was intended to grant constitutional protection against gender discrimination. Congress passed the ERA in 1972, but only 31 states approved the amendment. The Constitution requires three fourths of states to approve an amendment before it is ratified. A version of the ERA is still under consideration.

Changes to existing laws continue to address areas where discrimination surfaces in our society. In the years since passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, there have been advances in civil rights on many fronts, including race, gender, sexual orientation and identity. Many who argue that current manifestations of discrimination are not manifestations of systemic or institutional racism or sexism seem to feel that the many legal advances to this point have left only a problem with individuals who are racist or sexist or who act in discriminatory ways. These people seem to feel that, since they ascribe the problem to the individual level, there is no need for broad governmental action to address any perceived institutional racism.

This argument seems wrong to me because there is clear evidence that the effects of our social and governmental systems are still having a disproportionately negative impact on people of color and women. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 established the concept of “disparate impact” as a standard for determining whether a practice, policy or system was discriminatory. In employment, the standard is generally this: any practice that has a disparate impact on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin that is not job related or a business necessity is proof of discrimination. It seems to me that there is a clear disparate impact of our economic, social and legal systems on people of color and women. We can see this disparate impact in different life expectancies, incarceration rates, and levels of economic attainment. As the cases of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many others make painfully clear, we can see a difference in the rate at which civil authorities use force against people of color. Because the evidence of disparate impact is so clear, we must conclude that our systems and institutions still harbor, foster or tolerate racism and sexism.

There have been many attempts to address racism and sexism with legal changes over the years. None have been successful in addressing the whole problem. The fact is that the institutional problem we are confronting today is different than the problem that erupted in the Civil Rights movement of the twentieth century. The problems that exist in our institutions and across society today may not be as intentional or obvious as those addressed by previous generations. That doesn’t mean the problems are not institutional, systemic and serious. The argument from disparate impact indicates that they are all of those things.

The twin tragedies of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor’s deaths are but instances of a disturbing pattern that should be morally unacceptable to all Americans. The circumstances surrounding these and similar cases demand that we include a systemic and institutional focus as we address the symptoms of racism and sexism in individuals and in groups. Adopting a zero-tolerance policy on inappropriate use of force, coupled with an expanded role for de-escalation skills, community engagement and support activities seem the minimally acceptable steps to take at the level of our local government, law enforcement and educational institutions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed