An excerpt from Accountability Citizenship (Xlibris, 2013)

Certainly the President is the most common face of our government. News media regularly discuss the President’s views on major issues and every presidential action is a news story in itself. Not so with Congress. One Member of the House of Representatives and two Senators represent each American citizen in Congress. Yet many of us cannot discuss with certainty how members of our congressional delegation have voted on major issues. Much of what individual Members of Congress do is not subject to the same level of media attention that the President gets when he plays golf. It is no surprise that most Americans hold the President accountable for everything the government does or fails to do. But this perception is not consistent with a reasonable assessment of how we should view accountability for our elected federal public servants.

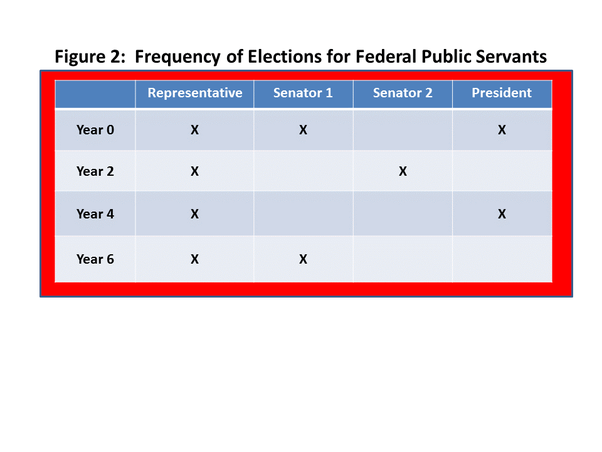

One would think that an official who had to seek re-election more frequently would be more accountable to voters than an official standing for re-election less frequently. Consider the frequency of re-election of Members of Congress versus the President. Every Representative stands for election every two years. One third of the Senate comes up for election every two years. Presidential elections occur every four years. So for every citizen, the opportunities to vote for federal officials over a six year period look like the pattern shown in Figure 2. On the basis of frequency of re-election, Members of the House of Representatives should be the most accountable of all federal elected officials.

Likewise, it seems that an official who represents 10 people should be more accountable to those 10 people than an official who represents 500 people or 5000 people. The President represents 50 times as many people as the average senator and nearly 500 times as many people as a Member of the House of Representatives. On the basis of the ratio between voters and elected official, House Members should be more accountable than either Senators or the President. In almost every case, Members of the House represent fewer Americans than Senators or the President. There is a unique Representative for about every 700,000 Americans today. Each Senator represents the entire population of their state, which means that Senators from the four states with the smallest populations[1] represent the same number of people as their one state Representative. But Senators from the most populous state, California, represent over 37,000,000 Americans. Most Senators represent some number of voters between 700,000 and 37,000,000. The President, of course, represents all 309,000,000 of us. In general, there is a better chance for Representatives to be connected with and accountable to the people they represent than for either Senators or the President. Yet on the basis of voting behavior, more of us take the time to vote for President than for either our Senators or our Representative.

It is no accident that Members of Congress seem to occupy positions that are structurally more accountable than the office of the President. There is ample evidence that the Constitution was written to make Congress—the legislative branch—more powerful and more responsive to the people than the executive branch. The Constitution addresses the legislative branch in Article I, with a few additional clauses throughout the rest of the document. Of the 4,446 words that make up the Constitution, 2,267 words—nearly 51 percent of the document—spell out the powers of the legislative branch. These powers include the sole authority for initiating acts that require expenditure of public funds as well as the authority to approve all presidential appointments. By contrast, only about 1,025 words describe the powers of the executive branch. The facts are that the President is generally able to do only that which has been authorized by Congress, and a majority of voters are not holding Members of Congress as accountable as the President for what our government does or fails to do.

Some will argue that we cannot hold individual Members of Congress accountable for the outcomes produced by either the 435 Representatives in the House or the 100 Senators in the Senate.[2] By this logic, some may consider the President more accountable because he is elected as chief executive and not as a member of a committee. I believe this logic is wrong for two reasons. First, the Constitution gives Congress the role of setting the agenda for the President, and not the other way around. Second, it is not the case that we must hold our Representative or Senator accountable for the entire corpus of work that is done or not done by the entire Congress. We must only hold them accountable for accomplishing specific, measurable goals we ask them to achieve. We must also hold them accountable for doing their part to stop legislation that is not in the best interest of all Americans. To establish individual accountability for Members of Congress, we must each communicate reasonable goals and standards to the public servants we elect to the legislative branch. I believe communicating such goals is both possible and necessary: my description of how we each can accomplish this essential task of citizenship comprises much of chapters 2 through 4 of this book.

[1] Alaska, North Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming; http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/index.html

[2] The problem of holding individuals responsible for collective outcomes is a classic problem of ethical philosophy. In practice, however, we can and do hold individuals accountable for their part in collective action. The ENRON case is a useful example. We must establish that for which our individual Members of Congress are responsible.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed